- Home

- News and insights

- Technology Investments

Investing in technology

Just too big? Will the technology titans hit a wall of regulation in 2021?

Among all the confusion and market volatility of 2020, tech companies shone out as a ray of hope. They achieved stellar performances during lockdowns around the world, stimulated by the move towards working at home and the need for tech to help us communicate with our loved ones, entertain us and ease our working practices.

At Canaccord Genuity, we naturally keep a close eye on all the tech companies. Technology is a massively powerful secular trend, so of course it has to be included in our clients' discretionary investment portfolios. While we can't ignore tech giants like Amazon, Apple or Microsoft, there are also plenty of smaller companies that provide interesting opportunities.

Even with the sector leaders, it is not as straightforward as simply placing all our bets on a hot tech favourite. There are many possible hurdles to be appraised and negotiated, such as regulatory curbs and ethical issues.

In this article (and video below), we look at the pros and cons of investing in tech – particularly the cons. Given tech's storming performance in 2020, are values likely to plummet in 2021? Will regulators try to break up the tech titans into more controllable chunks? Should we become too closely involved in Chinese tech companies, given China's record on human rights and the industry's vulnerability to government interference?

Size isn't everything – or is it?

There was a moment in the late summer of 2020 when just two giant US companies were worth more than the entire UK stock market. On 27 November 2020, between them Apple and Microsoft had a combined market capitalisation of £2.7trn, while the value of the whole FTSE All-Share was £2.2trn. It was a sobering thought for a country like ours that has long prided itself on hitting above its weight in the global stock market. A little more than six years ago, back in July 2014, the top five US companies were worth £1trn less than the FTSE All Share (which was worth approximately the same back then as it is today). In October 2016 these five became worth the same as the All Share, and are now worth fully £4trn more.

It wasn’t just the physical size of these technology behemoths that caused concern. Over recent years there has been an increasing fear of the power wielded by the top companies in this sector.

As consumers we are careless with our personal data, which we give away to the likes of Google and Facebook for free. After the Brexit referendum and US presidential elections of 2016 there was the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where data scraped from Facebook accounts was sold to the highest bidder. There were concerns over the ease with which Russian internet trolls might have influenced both votes. There were instances where advertisements for prestigious brands were placed in close juxtaposition with websites glorifying violence or pornography.

Added to this are the huge network effects that drive the largest technology companies. These give rise to virtual monopolies in social media (Facebook), in internet retailing (Amazon), in search (Google) and in operating systems (Microsoft). These near monopolies are replicated in China through Alibaba (internet retail, financial technology), Tencent (social media and gaming) and Baidu (search).

Increasingly, lawmakers across the world are focusing on the desirability of such power residing in the hands of a few, gigantic companies – the more so when many of them are adept at shielding their monopoly profits from tax. EU regulators in particular have pursued Apple (for tax), Google (for search dominance) and Facebook (for data collection practices).

Sharing knowledge – or spreading misinformation?

There are also profound concerns about the role of these platforms in amplifying fake news, spreading conspiracy theories and acting as forums for online hatred. When a group is caught in an echo chamber, there is little or no challenge to the prevailing view, which tends to become exaggerated – both on the right and on the left. The marked decline in bipartisanship in US politics is frequently associated with this phenomenon.

The perceived abuses of market dominance, the societal harm caused by the sheer size of the companies involved, the sense that these giant companies are now so big that they are becoming dangerous, have all engendered calls for increased regulation and even for them to be broken up. Many have used their market positions to buy up potential competitors; Facebook is perhaps the best example with its purchases of WhatsApp and Instagram, but Google with YouTube and even Amazon with its acquisition of Whole Foods Markets also show this trend. This has brought complaints of anti-competitive behaviour.

This isn’t the first time this kind of thing has happened. Microsoft faced an anti-trust suit in the US which lasted from 1998-2001. Initial judgements in the case called for the company to be split into two separate entities, with one side selling the Windows operating system, and the other selling applications and software, such as Internet Explorer and the Office suite of programmes. In the end the final compromise judgement was seen as a victory for Microsoft, as it was allowed to continue operating very nearly as before, although the company did assent to several relatively minor concessions.

However, the best template for breaking up a monopoly comes from much earlier.

Maintaining Standard

By the beginning of the 1900s, Standard Oil – the vehicle through which Nelson Rockefeller dominated the late 19th and early 20th century oil industry in the US – had become so powerful and controlled so much of the energy infrastructure in the US that lawmakers moved to break it up. In echoes of today’s debates, Standard Oil claimed that network effects (whereby consumers benefit from the economies of scale of giant businesses), better self-regulation and increasing competition would negate previous market dominance. In another similarity, a string of shady practices and scandals was sensationalised in the press at the time.

In the end, Standard Oil, which was the first company to record a market capitalisation of more than US$1bn (further echoes of today’s US$1trn companies), was indeed broken up into a series of regional oil companies, the so-called 'seven sisters'. For a number of years the uncertainty over the litigation leading up to the final decision caused Standard Oil's value to stagnate on the stock market, and indeed, it lost market share, from around 90% of all petroleum products in 1900 to nearer 60% in 1910. However, once it was split up, it didn’t take long for the combined value of the seven spinouts to exceed that of Standard Oil before the anti-trust case.

This carries possible lessons for investors in today’s debate. Using Facebook as an example, it is quite possible to envisage a scenario under which separately listed Instagram, WhatsApp and Facebook businesses might end up more valuable to investors than the original combined company. Or in Amazon’s case, whether, were regulators to force the separate listing of the rapidly growing Amazon Web Services business, investors might end up better off.

East is east

The issue of regulation has also raised its head in China, but here the dynamics are rather different. The Communist Party of China appears to have few qualms about the existence of giant companies per se, as the enormous size of the listed state-controlled banks there attests. It is when those companies become a potential source of conflict with the political and societal aims of the party that problems arise.

Recently, the US$313bn proposed flotation of Ant Group, the financial technology arm of Alibaba, was abruptly pulled the day before first trading, apparently due to intemperate comments made by Alibaba’s founder, Jack Ma, on the topic of regulation. Even though the Chinese regulators' objections were expressed in terms of Ant Group’s impact on the competitive landscape and on how to regulate the unofficial, so-called ‘shadow banking’ sector, it was clear from the timing of the withdrawal that political concerns were the main factor behind it. In other areas, two years ago, campaigns to curb excessive video gaming habits among young Chinese consumers had a marked impact on the underlying performance of Tencent, perhaps the nearest Chinese equivalent of Facebook.

This shows that Chinese regulatory pressure is expressed in a different way from ours in the West. In markets dominated by the rule of law, regulatory pressure is applied slowly through the legal system, and can take years to have an impact. In fast-moving technology markets, this can mean that by the time a problem has been addressed through the courts, the focus of market dominance has moved into other areas, as effectively happened in the case of Microsoft. In China, by contrast, action is swift and can be severe, as decisions are imposed by fiat.

This dichotomy reflects to some extent the way in which, though interconnected by global trade, it is likely that a different set of standards, both regulatory and technical, may evolve over coming years between technology companies in the Chinese and those in the Western spheres of influence. This strategic tension is likely to be a feature of the investing landscape for decades to come, and means that we increasingly need to think in terms of investing on both sides of the divide for our discretionary clients.

Finding a way through the moral maze

Of course, in an era of increased ESG (environmental, social, governance) focus, at least in the West, this may pose a moral conundrum to us as custodians of our clients’ wealth. For example, should we ignore what we in the liberal West would consider human rights violations, such as the fate of Hong Kong and the oppression of the Uighurs in Xinjiang, simply to gain exposure to growth in Chinese technology? Or, on the other hand, should we filter out such investments, which might reduce the opportunity set for our clients?

In either case, the increased focus on regulatory pressure on the tech titans comes at a difficult time for investors. This is because, after a stellar run of performance, valuations in the sector are high. This remains the case despite the recent rotation into more value-style names following positive news on coronavirus vaccines, and leaves the share prices of the tech companies vulnerable to negative surprises. It would be no surprise to see a pause for breath even without the pressure increasingly exerted on them by lawmakers and regulators.

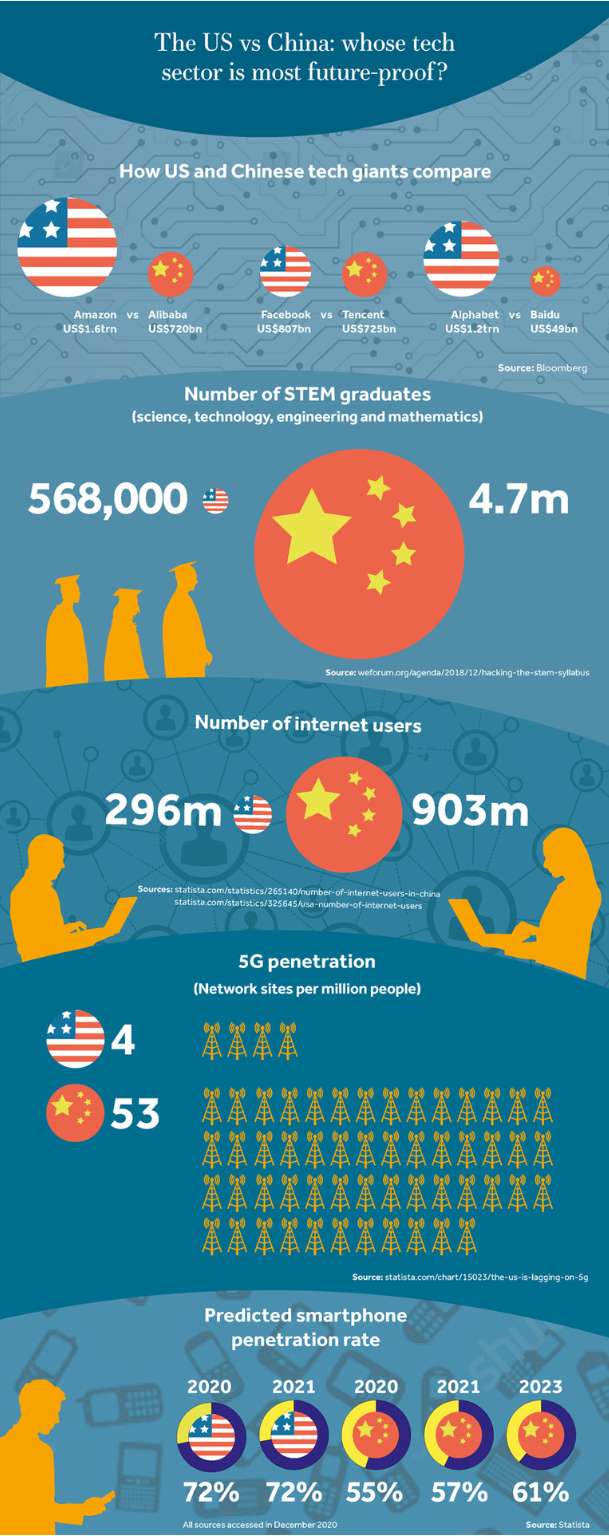

Please click the infographic below to see in full size.

Looking after your best interests

In all this focus on splitting up or controlling the largest names in technology, we must not lose sight of the very powerful secular trends that underpin the sector: the rise of artificial intelligence; cloud data storage; quantum computing; 5G mobile technology; robotics and factory automation; and the internet of things, among others. All these technologies are growing very rapidly – exponentially in some cases. Whether Apple, Alphabet/Google, Amazon, Facebook and the like can harness these trends themselves, the long-term attractions of gaining exposure to them remain in place.

Our Canaccord Genuity tech experts are constantly watching the sector, looking for new opportunities in companies from vast empires to small independent start-ups – and also keeping an eye out for lurking dangers. If you would like to talk to us about your portfolio, please get in touch with us or email wealthmanager@canaccord.com.

Read our other 2021 investment themes:

- Interest rates: the hunt for investment income

- Politically motivated – how politics and investments work together

- How COVID-19 is impacting the world of investment.

New to Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management?

If you would like to learn more about our investment themes for 2021 and what this could mean for your financial future, we can put you in touch with our team of experts that can help.

Investment involves risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the amount originally invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

The information provided is not to be treated as specific advice. It has no regard for the specific investment objectives, financial situation or needs of any specific person or entity.

This is not a recommendation to invest or disinvest in any of the companies, funds, themes or sectors mentioned. They are included for illustrative purposes only.

The information contained herein is based on materials and sources that we believe to be reliable; however, Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management makes no representation or warranty, either expressed or implied, in relation to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained herein. All opinions and estimates included in this document are subject to change without notice and Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management is under no obligation to update the information contained herein.

Find this information useful? Share it with others...

Investment involves risk and you may not get back what you invest. It’s not suitable for everyone.

Investment involves risk and is not suitable for everyone.